International

The Secret Newton

Autumn 2008

*The Kabbalist, Kimpen’s debut, has sold more than 60,000 copies

*Translation rights in ten countries.

Published by:

De Arbeiderspers

For information on translation rights please contact Michele Hutchison,

rights manager, m.hutchison@arbeiderspers.nl

Flemish Literature Fund

www.vfl.be

for information on translation subsidies please contact Greet Ramael,

grants manager, greet.ramael@fondsvoordeletteren.be

A Compelling Story of hard science, alchemy and desire

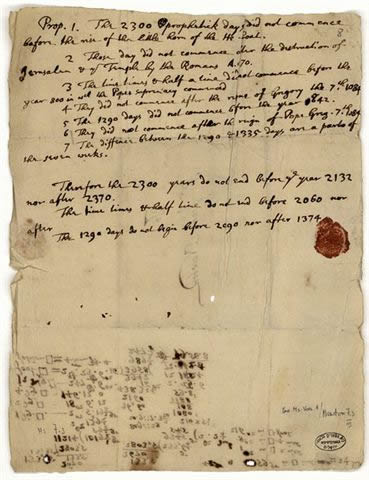

In 1717, Kit Conduitt, Newton’s niece, inherits a wooden chest full of manuscripts, notebooks, letters and diagrams. Bishop Horsley goes through it to see if anything is worth publishing. He slams the chest shut indignantly, “This chest should never be opened again,” he says.

Cut to 2008, for more than seventy years the chest’s contents have been puzzled over by academics but the results of their investigations have only trickled out bit by bit. Universities are in denial about Newton’s secret side. Now the world will finally learn what was in the box.

The Secret Newton is based on real historical documents from Newton’s chest.

Option holders: Goldmann (ge), Maeva (sp), Bazar (scand), Bertrand (por), Cyklady (pol), Päikesepillaja (est), Shabd (hin/eng), Humanitas (rom), Nova Gorica (slov)

Author Bio:

Author Bio:

Geert Kimpen (1965) is Flemish but lives in the Netherlands, he worked as a script writer before turning his hand to writing. He is the author of The Kabbalist and Step by Step, a guide to using Kabbalah to improve your life.

Press Quotes:

"A page-turning, enchanting story, which you also learn a lot from. Geert Kimpen is a better writer than Dan Brown. He shows a different side of Newton, a man who really comes to life in the book..."

- Good Morning Netherlands (TV)"A perfectly-constructed story. It's evocative, fast-paced, educational, interesting and the author's passion is tangible in every word. This book demonstrates the growth the author has made since his debut, The Kabbalist and this, his second novel; growth in many different areas: this novel is more complex and more philosophical. In The Secret Newton, Geert Kimpen opens a dialogue with his readers."

- Blanco Regel (literary magazine)"A thrilling, spiritual novel. A saga, a mixture of fiction and fact with an exceptional depiction of the character of Newton, his understanding of Biblical exegeses and his role in founding the Freemason's guild in England."

- Biblion (public libraries)"The Secret Newton won't disappoint Dan Brown fans. Newton's life provides wonderful material for a fantastic historical novel."

- De Standaard (Flemish broadsheet)"A rising star, Geert Kimpen - our very own Dan Brown. It's exciting for sure. The Secret Newton won't disappoint."

- Bladwijzer (TV programme)"Actually, with The Secret Newton the author has invented a new genre. Its characteristics are a story than reads like a thriller, a biography of one of the greatest physicists of our time and as an extra, the revelation of an age-old, profound form of knowledge. Dan Brown and The Secret haven't got anything on it."

- Recensieweb (website)

The Secret Newton - Geert Kimpen Synopsis

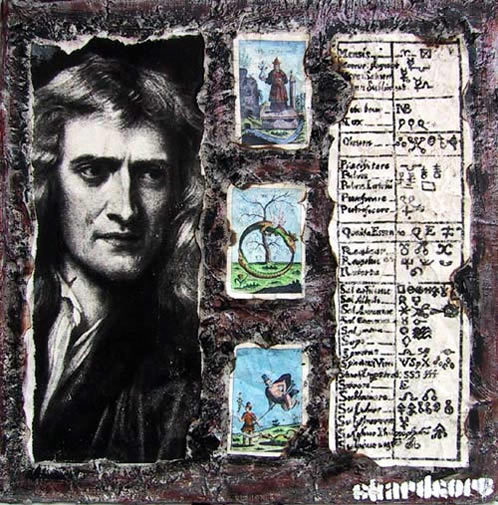

The Secret Newton is set in 18th century England against the background of the dawning age of the Enlightenment, Europe’s emergence from the darkness of the Middle Ages and the struggle of the old political world, with its theocracies and monarchies, to survive the transition into modernity. It is based on unpublished archive material about one of the world’s best known men of science, Sir Isaac Newton. Kimpen combines meticulous archive research with gifted story-telling to weave a sensitive yet revealing portrait of a side of Newton unknown to the general public.

The Secret Newton is set in 18th century England against the background of the dawning age of the Enlightenment, Europe’s emergence from the darkness of the Middle Ages and the struggle of the old political world, with its theocracies and monarchies, to survive the transition into modernity. It is based on unpublished archive material about one of the world’s best known men of science, Sir Isaac Newton. Kimpen combines meticulous archive research with gifted story-telling to weave a sensitive yet revealing portrait of a side of Newton unknown to the general public.

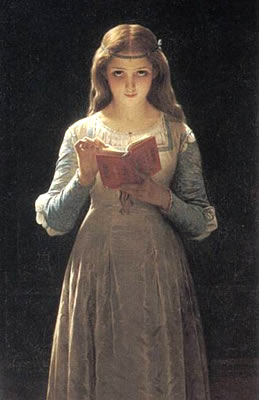

The story is told from the perspective of an unidentified narrator and covers important and transitional moments in Newton’s life – from his initial years as a shy and unnoticed Cambridge professor, through his years on the family farm after the death of his mother, to his return to Cambridge and a life prominence. Flashbacks to his unhappy youth and insights into his complex personal and relational life combine with better-known historical material to reveal a man of genius ready to embrace the rationality of the modern world yet unable to abandon the esoteric ambitions of the passing era.

The Secret Newton ends with Catherine (Kit) Barton and her husband John Conduitt presenting a chest containing the documents of Kit’s deceased uncle Isaac to Thomas Pellet, a member of the Royal Society. Pellet determines most of this archive ‘absolutely unfit for publication’. Theses documents are Kimpen’s primary source.

The Secret Newton reveals the personal life of the author of the “Principia” as a tortured and complex counterpoint to his public existence. The novel’s background is riddled with the machinations of politicians, monarchs and popes, all of them set on power and wealth. Even the academy – including Robert Boyle, John Locke, and ultimately Newton himself – is unable to escape the lust for influence and prestige, urged on by the blind desire for supremacy and wealth of Europe’s political and religious leaders. Aristocrats, alchemists and academics unite in The Invisible College (and later the Lodge…) in search of esoteric knowledge, the elixir of life, the ability to create gold, and the fulfilment of their desires.

The book’s characters are designed to reflect the complexity of Newton’s private life and its conflicts – his remote father, his hateful mother and manipulative half-sister Hannah, his ‘romantic’ attachment to John Wickens as a student at Cambridge, his failed engagement to Catherine Storer, his love for Nicolas Fatio de Duillier, the mysterious temptations of Saint Germain, the scheming Jonathan Swift, together with a host of royals, whores and both major and minor academics – the character of his niece Kit representing a thread of purity and simplicity running throughout the book.

Some have argued that Isaac Newton was the first representative of the Enlightenment, but Kimpen’s research reveals that in spite of his masterful insights into the laws of nature he also had alchemistic ambitions and unorthodox religious beliefs profoundly rooted in the very ideas the Enlightenment set out to reject. The book thus interweaves Isaac’s scientific genius with his alchemistic convictions and kabbalistic inspiration, design and reason with nature and eros.

The narrative culminates in Isaac’s appointment as Master of the Mint and his ambitious plan to establish a gold standard in an effort to stabilise England’s economy in the midst of a warring Europe. This, and not alchemy, is where he hopes to succeed in producing gold in endless supply. Yet politics – his country’s need for gold – and blackmail – Jonathan Swift threats against his lover Fatio – draw him back to alchemy, the quest for the Philosopher’s Stone and the secret of creating gold.

The book’s base note is the power of gravity, attracting objects large and small, but also attracting hearts. The book exposes Newton’s tortured secrets: wounded by his mother’s rejection, drawn to other men by nature yet forced by propriety to live a false life, tempted by ‘demons’ to explore and realise the seven stages of alchemy, yet inspired to explore and explain the laws of nature, loyal to king and country, forced to betray his beloved Fatio, unable to protect his niece Kit from the tentacles of the mysterious Saint Germain and Swift’s Hellfire Club. Isaac ultimately finds resolution in the awareness that alchemy and life go hand in hand, that they are both a process of purification into gold. In the end, Kit is able to free herself from Swift – who is banished to Ireland – and save Fatio from the executioner. Isaac is finally reunited with his one true love.

*****

Extract translated by Brian Doyle [biblostrans@yahoo.com]

Chapter 11

The hand Isaac caressed felt like a messy pile of chicken legs, picked to the bone and cold. It was a hand he had once feared for the ruthless blows it had dealt him, but now it rested on the blanket like a piece of kitchen waste. She had a serious look on her face. Even as she slept, an angry frown marked the thin, translucent skin of her exceptionally high forehead, a patch of flesh without lustre or resilience that no longer tried to disguise the blue veins and brown specks of old age. Her skin was tired, ravaged and torn by life. Her thin grey hair was greasy and tied up in an austere bun. Her bloodless lips were pursed boldly together and silent. Her moribund corpse was taut with rage and bitterness. He sat at her bedside for hours on end, from the moment he had arrived. Her bedroom had always been off-limits to him. The very idea of touching the door handle had never even crossed his mind. Even now he felt like an intruder in this room full of sickness, dissatisfaction and disappointment.

Isaac jumped every time she gasped for breath with the desperation of a drowning man, his lips emerging for a fleeting moment above the foamy waves. Fearing the pile of bones might come to life and treat him to a blistering slap on the cheek, he turned his face. Here, in this same oak bed, his father – an illiterate ghost from the past that refused to be grasped – had turned his back on life. He had searched for the man’s contours in the mirror, but found nothing consistent. His aristocratic nose and clearly defined lips were unmistakably those of his mother. Whatever had attracted her to his father, a tormented gentleman farmer, remained a mystery to him. The servants used to say he could lift a pregnant cow into the air with his bare hands. He was a tree of a man, felled by a single innocent tick bite. He must have been a good farmer, a man of few words who worked hard all his life. He was already thirty-five when he married my mother, one of the distinguished Ayscoughs. She moved in with him. His fertile farmer’s seed impregnated her here in the spring, but by the summer he was poorly and the seriousness of his illness quickly became apparent. He made a will, leaving the farm, its 234 sheep, 46 heads of cattle and savings to the value of five-hundred pounds to his newly-wedded bride and sealed it in ink with his thumbprint.

He spent the sultry summer days of her pregnancy in bed, sweat gushing from every pore. It must have been by the grace of God that he returned to his maker at the beginning of autumn, allowing her to attend to her own needs in the final weeks of her pregnancy instead of dabbing her husband’s forehead with hot and cold herbal compresses. She had not cried that sunny 6th of October, the day her husband’s colossal corpse was confined to its grave. Even the gravediggers heaved a sigh of relief, content that none had suffered injury from having to dig such an enormous pit in the arid soil. The few anecdotes Isaac had collected at the funeral – proffered like alms by the charitable – weren’t enough to fill a gravestone, let alone compile a sketch of his father’s life, however brief. His father was a short sentence cut off in midstream and followed by pages of white. He drifted in some vague, undetermined place above him, like a sun it’s impossible to look at without being blinded.

His mother was indifferent to the spawn fermenting in her womb and awaited the birth with resignation. The contractions started on Christmas Eve, pitching into her swollen belly like tidal waves. The maid had been sent out into the snow to fetch the midwife from the village, tearing her away from her Christmas dinner. ‘Come back tomorrow,’ the woman had said. ‘There’s nothing I can do for her tonight. Happy Christmas.’ But the maid had barely dusted the snow from her winter coat when the baby announced its arrival in a screaming, blustering, bellowing, and bawling flurry. A deathly silence followed. He came into the world on Christmas Eve, here in this dark-stained bed with its faded curtains and wooden posts, his birth seemingly obedient to the laws of alchemy. Nature first brought death and decay before it made way for new life. His father’s corpse had decomposed and its bodily juices had leaked into the dark soil, but now the remaining brown sludge dissolved and evaporated, swelling the tiny sacs of air in the lungs of the newborn to their limit.

The world died incessantly only to be reborn. The earth was a massive steaming and snorting animal, breathing in the ether of death’s fermented mire. His mother had stared with revulsion at the blood-drenched clump of flesh she had birthed. A tiny, ugly piglet, which could only be counted part of the human race with considerable imagination. Where is the rest, she had thought. Perhaps this was the afterbirth and the baby was still on its way? But nature had given enough. ‘Such a measly thing… you could fit it in a jam jar,’ was all the maid could splutter. When an opening suddenly appeared in the sticky slime covering the freak’s eyelids, both women gasped with horror. It was alive. A pair of smouldering charcoals stared back at them accusingly, as if to say ‘Did I ask for this? What’s going to happen to me?’ and buttressing its demand for attention with a monstrous screech.

‘I suppose we should fetch the midwife,’ his mother had said. The maid was not in the mood for the long walk to Lady Pakenham’s house for medicine and did not budge an inch.

‘Back through the snow in this wind?’ she had snarled. ‘Not likely! Let’s be honest: this bag of bones isn’t going to last the day. Do you want me to catch a cold?’

His mother had nodded understandingly. What was the point? Just before she fell asleep she heard the church clock strike two. Come and gone on a white Christmas. Has something of a ring to it, she thought to herself. The tiny creature dwelt in the kingdom of shadows for three whole days, a pillow folded around its wrinkled head to stop its fragile neck from cracking like the branch of a tree, but the tiny clot of flesh and blood did not give up. On the fourth day it rallied, and by December 29th it became clear that a new Newton had joined the world’s population. Only then was he given a name: Isaac, Hebrew for ‘he who laughs’. Isaac Newton, an unwanted, fatherless boy with little to laugh about. Years later he heard that Galileo Galilei had breathed his last on that selfsame day, December 29th 1642. It was as if the gods had taken the Promethean fire that had enlightened all humanity from Galileo and assigned it to a talented boy in a snow-covered farmhouse in Woolsthorpe, all part of nature’s eternal cycle, initiated by God himself. Isaac was finally considered strong enough to be baptised on New Year’s Day in the family chapel on the estate.

Now he was grateful that celestial providence had taken him by the hand and lead him home, grateful that he could be with his mother in her final hours. Although she had never been there when he needed her, he wanted to be there for her. He had said his farewells to her once before, but perhaps this time it would be different. Perhaps this time she would be gentler. Isaac wandered in thought to the cellars of his early childhood. There was excitement in the house, expectation, a smile on his mother’s face, a rare event. He burrowed deep into the folds of his memory in search of a reason for her happiness. Did it have anything to do with him? Had she ever been cheered by anything about him? He thought it unlikely. Suddenly he remembered that he was three years old and his mother had received a proposal of marriage.

Her elderly admirer had submitted his request in writing, short and to the point, and hadn’t even taken the trouble to deliver it in person. Isaac remembered the lightness that filled the farmhouse at the time, his mother dancing through the kitchen, her eyes aglow, something he had rarely witnessed. ‘The very idea that a man might still have an interest in me…’ she told him years later with the same sense of surprise. She was a woman of thirty, after all, and with a child…, not the most attractive option for potential suitors. Her brother tried to temper her enthusiasm and checked the man’s background. Barnabas Smith turned out to be the Reverend Barnabas Smith. He was not handsome, nor was he young, but he was a man of substance, a sixty-three year old minister from nearby Witham who had himself been widowed six months earlier. The absence of children played in his favour, but it wasn’t long before her brother heard stories of his miserly and inhospitable nature.

His mother insisted on entering into negotiations nonetheless. Barnabas tabled the first of his demands: he wasn’t interested in the young Isaac and insisted he stay on the farm. His mother countered with a demand that Barnabas carry the cost of a new roof for the farm and he agreed. When the old miser finally, if grudgingly, consented to transfer a piece of land to Isaac on his twenty-first birthday, his mother accepted his proposal of marriage without further ado and moved in with her new husband. She left her child behind with a roof over his head and ground beneath his feet. What more could he have expected from her? There was little he could do the day she left. She waved excitedly from her carriage, a cantankerous old man stooped over the reins by her side. He stood outside waving at the desolate gravel path until dusk. His grandparents refused to answer his questions. Where is mummy? When is she coming back? Why can’t I go with her?

The first time he asked these questions they withdrew in silence, but later they rewarded his curiosity with a clout. Life was like an unwelcome guest; you just had to make the most of it. They hadn’t asked for this. Wasn’t it time to stop asking why, when, where? They had as little interest in little Isaac as his mother. What were they supposed to do at their age with a three-year-old monster vying for attention day in day out? Their duty as Christians obliged them to raise the boy, but no more than that.

His grandfather did what was expected of him in the years that followed: he taught young Isaac all he needed to know to be a gentleman farmer. The quicker the boy learns his trade, he thought, the sooner I get to enjoy my old age. Nonetheless, he was pessimistic, Isaac was clearly clever, but he lacked interest. He was a dreamer. His grandfather tried to shatter his illusions at every turn, but Isaac was obstinate. During his mother’s annual visits – an hour or, by exception, an entire afternoon – his grandfather did nothing but complain about him. He was good for nothing and he was going nowhere.

Perhaps her imminent death would bring them closer together? He wanted to tell her about his professorship, that he had met the king, that he was close to a major discovery, that he had done well in spite of everything she had said to the contrary. More than anything, he wanted to ask forgiveness for that terrible passage in his boyhood diary, his diabolical plan to set the house in which his mother lived with Barnabas ablaze and his carefully recorded scheme to block the door and prevent them from escaping.

His mother had locked him in his room after his grandfather read these lines to her on one of her visits. He and his mother had only been together for three minutes that year. Isaac wanted to tell her it had all been boyish nonsense, a twisted declaration of love for the mother he had missed so much. But she remained expressionless, closed, as if she were determined to evade him, to have nothing to do with him, even now.

His now emaciated and decrepit mother had borne three other children to Barnabas: two half-sisters and a half-brother, with whom he was suddenly forced to share the farm when Barnabas breathed his last fetid breath after eight years of marriage. His grandparents moved out and his embittered mother took charge once again. Her eight years of absence had eaten away at the slender umbilical cord that bound them. They argued every day and Isaac always took second place when it came to the stepchildren. Only Hannah, the eldest daughter, had written to say she was on her way to see off her dying mother.

Would she open her eyes for Hannah? He prayed for a moment alone with his mother before she arrived, fearing he would revert in her presence to the little boy who was used to ducking under, protecting his head with his hands; the boy who had been warned good and proper that if he didn’t listen to his grandfather his mother would put an end to her visits. The mother with the withered hand that now rested in his, the hand that had dealt only blows and never caresses.

Chapter 12

‘Yes,’ the lady said, her eyes pinched shut as if she hadn’t seen daylight in months, ‘interesting, interesting. So you and Isaac are friends. I see. How extraordinary.’

She peered timidly left and right through the crack in the door at the rain-drenched street outside.

‘Come inside. Quickly,’ she whispered, and she pulled John by his jacket into the narrow hallway and closed the door behind him. She dismissed her odd behaviour with a hoarse chuckle, and remained standing apologetically, looking him up and down, her eyes still pinched together.

‘Interesting,’ was all she could say, ‘interesting.’

Suddenly aware that her blue dressing-gown had fallen open to reveal her flesh-coloured nightdress, and realising she was standing in corridor half-naked with a complete stranger, she pulled her dressing-gown shut with exaggerated arm movements, like a curtain closing on a theatre performance.

‘Yes,’ she laughed knowingly at her absent-mindedness, as if she had wanted to say: ‘I’m one of those.’ John stared at her, puzzled.

He had hesitated for days before finally daring to visit the pharmacist’s daughter. Isaac had warned him that his mother would not approve of a stranger in the house, prompting him to rent a room at the George Inn in Grantham, about six miles from Woolsthorpe. He wiled away the long empty days waiting for news of Isaac by visiting all the places they had talked about. It stopped him from brooding and kept his darker thoughts at bay, his lonely struggle to get back to a time when everything was normal, a time he had wanted to last forever. He had always envisaged a tranquil, predictable future for them both, living together like an old couple, close, caring for one another. ‘The only certainty is change,’ Isaac had once said, quoting Heraclitus. He had been right, as usual.

Her head hung, Catherine made her way down the passage to the living room and John followed. The room was the worse for wear, neither opulent nor cheerful. The armchairs were threadbare and the crockery cabinet’s glass door was cracked.

‘So,’ said Catherine, ill at ease, ‘you have a message from Isaac?’

‘No,’ John replied. ‘I actually came for you.’

Her eyes opened wide with innocent surprise, but she quickly resumed biting her lower lip. She closed the curtains and left the room. John heard a door being locked and the nervous jingling of cups. His rain-soaked jacket dripped onto the grimy carpet. Just as he was contemplating a quiet exit, Catherine reappeared with a tray and offered him a cup without a handle perched on a faded saucer, trembling and still apologetic.

‘You like tea, don’t you?’ she inquired and sat down. John noticed that her own cup was an even sorrier sight.

‘I’ve been waiting quite some time for an answer to a couple of my letters,’ she said, shuffling her bare feet. ‘All of twenty years, if I’m honest. I don’t mail them anymore, but I haven’t stopped writing. I write one every week. Perhaps you could deliver them for me?’

John remained standing, stirred his tea, cleared his throat and said: ‘I’m afraid that would be difficult at the moment. Isaac is in Woolsthorpe and prefers not to be disturbed for the time being. His mother is sick.’

‘Is his mother sick?’ she asked slowly, her pupils gliding absently upwards.

‘Come,’ she said, inviting John with a wink to join her on the couch. She pinched her eyes together once again to get a good picture of his face. A radiant smile appeared on her lips and she breathed in through her nose as if she recognised Isaac’s smell on John. John noticed her welcoming lips and sparkling teeth for the first time. Her flaxen blonde hair, which tumbled constantly over her face only to be brushed out of the way with a flick of the hand, disguised the sort of beauty that only tends to reveal itself at a second glance. She took his hands and rested them on her lap.

‘It’s such a delight to meet someone who knows Isaac,’ she said. ‘No one talks about him anymore here in Grantham. I’m grateful for your visit, although… Never mind, what difference does it make?’

‘Were you good friends?’

She glanced furtively around the room to be sure no one else was listening.

‘You ought to know,’ she whispered, gazing at him intensely with her bulging round eyes, ‘Isaac wasn’t exactly everyone’s favourite at school. At that age it’s muscles and bravura that impress, not brains. It’s a lonely business being different, I can tell you. He rented a room from my stepfather and we spent a lot of time in each other’s company. He taught me carpentry. We even made furniture together for my doll’s house. I played with him out of pity to begin with and even offered him some affection on occasion. After school he would read alone in his room or help my stepfather in the pharmacy. He was useless, really. Brilliant perhaps, but useless, especially when it came to other people.’

John nodded in agreement. No one’s heart was more impenetrable than Isaac’s. John had dismantled the walls he had built around it stone by stone, but an open door could slam shut at a single hurtful word. John had grown accustomed to his ways through the years and they had turned out to be one of his most endearing features. Infatuation is drawn to the splendid, but true love learns to appreciate the less than splendid.

‘With two brothers and Isaac in the house I ended up a bit of a boy myself,’ said Catherine, as she cleared the cups and a marble statuette of Venus from the table in front of them and turned it over. ‘Look at this,’ she said, ‘the legs collapsed last week but I managed to fix it. Not bad, eh?’

John agreed, it was a fine piece of carpentry. He turned the table back on its feet as Catherine disappeared into the corridor. She returned a moment later with a reassuring nod, fastening her dressing-gown apologetically for a second time.

‘We were working on a miniature watermill by the river,’ she said. ‘Isaac had trained a mouse to tread the wheel. He started on about rotational energy, but I held my finger to his lips. I produced a poem from my blouse that I had found in his room, a love poem, written in his best handwriting. “What’s this,” I said sternly. His face and neck turned every shade of red and he stuttered and stammered. I put on my preacher’s voice. “If you ask me this is a love poem. Is there a girl in your live deserving of such words? She must be a goddess. Why haven’t you spoken about her?” He finally confessed in fits and starts that I was the subject of his poem. That was when I kissed him.’

Catherine collapsed into the couch beside John. She closed her eyes and pondered out loud: ‘They say a girl can tell at first kiss if a boy really loves her. Perhaps there’s not enough girl in me, but I didn’t feel a thing. It was more of a fuss than anything else, really. The same happened with other boys when I got older. It’s possible, of course, that none of them really loved me.’

She laughed at herself and then became serious: ‘Forgive me for telling you all this. It’s nonsense, I know, but the house can be so silent and I rarely get a visitor. That’s why I’m inclined to babble so much.’

‘No, please, it’s my fault for being so inquisitive,’ said John, saddened by her account of youthful love and this first kiss, which had stolen and not he. ‘So you finally married someone else?’

She leered at him and carped: ‘If getting married means saying “yes” in front of packed church to a man chosen by your stepfather then yes, I married someone else.’

She lifted the table out of the way, pulled aside the faded carpet beneath it, and opened a hatch concealed in the wooden floor.

‘Carpentry comes in handy now and again,’ she said with a grin. The hidden compartment was brimful of letters in envelopes carefully address to the university of Cambridge and tied together in bundles. ‘Or is this more like marriage?’ she asked. ‘What do you think?’

John stared in amazement at the secret treasure. He remembered the letters Isaac had received every day when they first shared rooms. He recognised the neat girlish handwriting. ‘What are you doing?’ he once asked. ‘Why throw them away without reading them?’ ‘They’re from a girl,’ Isaac had answered. ‘I don’t have time for that kind of twaddle.’ They never spoke about it again after that, but Isaac had demonstrated his fondness for John in ignoring the letters and their friendship had evolved at that moment into love. John stared at the woman as she knelt beside her secret vault and pored over one of her letters. The absence of cosmetics and her scattered behaviour gave her and unsophisticated charm. She and John both loved the same man.

‘Was there a reason for your visit?’ Catherine asked out of the blue, but before John could even begin to answer, the bell rang in the corridor and she was visibly startled.

‘Help me, please,’ she said, running her fingers through her lifeless hair. ‘Put everything back as it was. How do I look?’

‘Good,’ John nodded unconvinced. He quickly closed the hatch and slid the carpet back into place.

‘It’s all I have, Mr Richards, believe me,’ he heard Catherine plead from the corridor. Seconds later, a corpulent man stormed into the parlour. He glowered disdainfully at John, who did his best to appear relaxed.

‘And you are?’ he barked.

John stood and offered the man his hand.

‘John Wickins.’

‘Mr Wickins is a friend. We were just reminiscing about old times. Please take a seat, Mr Richards, while I fetch the rent.’

Richards plumped his cumbersome, rain-soaked bones next to John on the couch.

The men sat in silence as Catherine hurried upstairs. John sought franticly for something to talk about, but the man’s distinguished appearance intimidated him. He was wearing a tall black hat, a splendid, if gallingly blue velvet doublet and breeches, and highly polished shoes with gaudy ribbon laces. John winked awkwardly at Richards, prompting him to shift himself ostentatiously to the furthest end of the couch. Catherine finally came downstairs and produced five pounds from a lady’s purse, which she counted out on the table in front of Richards. He remained indifferent.

‘And the rest?’ he grunted.

‘This is all I have, I assure you.’

‘You’re forty-five pounds in arrears and you give me five? Mr Wickins,’ he turned to John and continued derisively, ‘if I’m not mistaken that’s forty pounds short.’

John rummaged obligingly in his trouser pockets and placed two gold one pound coins on the table.

‘You know my husband, Mr Richards. Business was good for a while, but the last couple of months… I do what I can to help when he’s, you know…’

‘Did you ever stop to wonder why your husband does what he does? If I caught my wife in her nightdress on the couch with a strange man… A woman ought to be a home for her husband. Is it surprising that a man is inclined to stay away when his wife opens the door to all and sundry? I think it’s time I found respectable tenants, irreproachable tenants. I want you out of the house by the end of the month.’

He grabbled the seven pounds from the table, dropped them indifferently into his coat pocket, heaved himself from the couch and lumbered towards the front door. Moments later Catherine reappeared evidently unperturbed.

‘It was such a pleasure to talk to you, but I really should be getting on. A woman’s work is never done. You can find your own way out?’

14

Isaac spent nights on end at the desk in his old room, sifting through the cash ledger by candlelight. Immersing himself in numbers felt like taking a lukewarm bath in the spring. Beautiful concrete numbers representing tangible pounds rather than unfathomable quantities, like the distance from the earth to the moon. Numbers had an epic quality, and the ledger that had been maintained to the last penny from the moment his mother married his father told the story of her life. The first pages contained hesitant, obstinate and unassuming numbers, hanging their heads at the death of his father. They cast aside their aristocratic blue for gallows red.

Here and there a dried up tear made the red ink difficult to read. Unlike some of his colleagues, Isaac liked negative numbers, in spite of the claim that God had only created positive numbers and the negatives were the work of the devil. Others even wrote them off completely as numeri absurdi. Negative numbers were mysterious because they did not have an equivalent in reality. ‘Three apples’ was easy enough to grasp, but what about ‘minus three apples’? Negative numbers seemed to offer a glimpse behind the curtain of the anti-world, revealing a sort of antimatter with a visibly reversed component in an alternative, unobservable reality. They were only to be grasped in abstract concepts. As he had once read, the key to concocting the elixir was to be found in the anti-elixir.

The infiniteness of the universe was just the same, its impenetrability best approached by a study of the infinitesimally small. If you divide zero by two you ended up, mathematically speaking, with twice as little as you would if you divided it by one instead… It was an absurd argument, but it had preoccupied him for years. Alchemy had taught him that whatever argument applied to the greater also applied to the smaller.

It was only after his mother’s second marriage that the numbers in the ledger crawled above zero, like a man pulling himself out of the waters that had almost claimed his life. These pages were written in his grandmother’s hand. His mother’s marital negotiations had resulted in something of a breakthrough and the numbers increased at a gradual yet confident rhythm to reach the positive opposite of their lowest ever ebb. They finally took flight after the death of Barnabas, his stepfather. Once again in his mother’s handwriting, the numbers blossomed with health and self-confidence. He read to his surprise that his mother had booked an annual income of more than seven-hundred pounds while he was at Cambridge, a painful contrast to the fifteen meagre pounds she allowed him every year for his upkeep.

In the years that followed, the numbers became more and more exuberant, tumbling upwards in an effort to exceed one another, only to fall dramatically a few months prior to his visit when his mother had taken ill. It took him a couple of nights to work out the whys and wherefores of this downward swoop, but numbers never lied, he was sure of that - that was why he loved them so much and could wile away the hours in their company.

Nothing gave him more pleasure than a calculation that tallied. God expressed himself in numbers. No other language was precise enough to say what he wanted to say. Words had nuances, were open to different interpretations or inaccurate translations, but numbers were universal, they ether tallied or they didn’t. And the story numbers told revealed the perfection with which God had created the universe in all its beauty. Numbers used a plain language devoid of pomposity and spoke the truth in simple terms, just as the simple accounts here in this ledger revealed the truth about a farm in Woolsthorpe. By dissecting the numbers with the precision of a scalpel one could expose the tumour.

The mistress of Woolsthorpe’s illness had spurred a brood of vultures to withhold payment on their debts. He wrote them threatening letters with enraged fervour, established uncompromising deadlines and warned that refusal to settle would lead to court proceedings. The only bills he set to one side were those of Catherine Storer. He thought it inappropriate that the first sign of life the pharmacist’s daughter had received from him in twenty years should be a demand notice. But he still found it difficult to understand how the years had brought her to such depths, and tried to concoct an alternative way to collect her overdue payments.

When Kit proudly presented him with a sundial she had made that afternoon, its needle a carefully stripped and painted twig, he was touched.

‘Let’s see if you were paying attention, Kit,’ he said in a schoolmasterly tone. ‘Where should we hang it to get the best results?’

The girl furrowed her brow and looked at the sun.

‘If the shadow points north it must be twelve noon,’ she said pensively, ‘that means the sun is to the south… In the south then?’

‘Correct,’ said Isaac. ‘But we have a problem. None of the walls here on the farm is exactly south-facing. You’ve drawn a symmetrical clock face right and left of the needle, but if we were to hang it up on the most south-facing wall…’

‘It wouldn’t work,’ Kit interrupted, clearly disappointed.

‘It’s best to draw a sundial on the very spot you plan to hang it,’ said Isaac. ‘Believe me, it took me several attempts before I managed to figure it out. But that’s how you learn about nature, Kit, by experiment. When your experiments don’t turn out as you had hoped, then you have to ask yourself what you did wrong then try again, learn from your mistakes. Nature has all the answers. The sun does the same thing every day, and if we look carefully and think about what we see we can begin to understand nature and the way God keeps everything in motion.’

Their conversation was abruptly interrupted by Hannah’s dreadful voice, bellowing from an upstairs window: ‘Isaac! Isaac! Get up here, good-for-nothing…’

Isaac and kit hurried upstairs. His mother had turned yellow and was shuddering and quivering in her bed, uncontrollable spasms contorting her limbs and sweat gushing from every pore.

‘Hold her arms,’ Isaac shouted. ‘I’ll fetch a sedative.’

‘No, stay here!’ Hannah screamed. ‘She’s choking. Her tongue is doubled over. She can’t breath. You hold her and I’ll try to open her mouth.’

But the frail old woman’s jaws rattled and Hannah’s attempt to free her mother’s tongue with her with her fingers only made her retch. Her hollow belly tightened and her gastric juices rushed upwards through her gullet and into her mouth. She was drowning in her own vomit.

‘Sit her upright,’ said Isaac, ‘she’s choking!’

The helpless old lady stared wide-eyed at her children as they tried to unblock her throat and control her spasms.

‘You try, Isaac. I can’t do it. Damnation!’ said Hannah, angry at herself.

Isaac tried to prize open his mother’s jaws in an effort to free her bleeding tongue, but her pointed rotten teeth bored into his fingers forcing him to pull back his hand. Then he caught sight of Kit.

‘Kit, hurry, fetch the needle from the sundial. We can force it between her teeth.’

The girl raced downstairs and into the courtyard, but hesitated when she saw her sundial lying on the grass. She had spent so much time on it. It had been her secret. She wanted to win her uncle’s respect, the same uncle who had insisted for days on end that there were more things in life than a clean house, that a girl’s intelligence was every bit as important as her appearance. She wanted to show him that she could do more than mop the floors. But if she broke the needle from the sundial she would have to start again from scratch. She hadn’t even had the chance to show it to her mother. She ran to the orchard in frantic search of another twig, but the orchard had been tidied up and she wasn’t strong enough to break a twig from one of the apple trees. She looked around in panic to see if anyone nearby had a shovel or broom in hand, but the farmhands were off grazing the sheep and the servant girls were eating their midday meal in the spring sun on the other side of the river. She hurried back to the sundial and took a deep breath as the crack of the needle tore her dreams asunder. She ran to the farmhouse and slowly climbed the stairs, her eyes moist with tears.

Her grandmother lay still in her bed and Isaac sobbed in silence at his mother’s breast. The words of appreciation he had longed to hear were now forever beyond his reach. Even the expression on her face as her life slipped away and her eyes clouded over was full of reproach. Her vitality also disappeared with her last breath. Her mortal remains were nothing more than a silhouette of the woman she had once been. They resembled his mother but she was no loner present. He asked himself if her soul had cast off her body like a garment and been taken up into the universal cosmos. But where had it gone? Where was heaven? Would humanity ever be able to build a telescope powerful enough to see the kingdom of heaven? Or was heaven a reflection of the mysterious anti-world, the unimaginable world of negative numbers, an alternative reality our senses and imagination were unable to grasp? Perhaps death was death and nothing more, a return to dust and ashes, a time of waiting in the vaults of the earth for a Messiah to appear who would raise the dead to life and judge their deeds?

Hannah was slumped on the floor next to the bed, crushed.

‘Please forgive me, mummy. I looked everywhere for a stick. I did my best. I’m sorry, mummy.’

Hannah lashed out as if to cuff her daughter’s ear, but she missed her target. She wasn’t interested in her daughter’s guilt. Their mother was dead, choked in her own vomit, and they had both failed her. She had died as she had lived: fighting to the last, refusing to accept fate, the death of a gentleman farmer’s wife who had always considered herself a baroness.

*****

Published by:

De Arbeiderspers

For information on translation rights please contact Michele Hutchison,

rights manager, m.hutchison@arbeiderspers.nl

Flemish Literature Fund

www.vfl.be

for information on translation subsidies please contact Greet Ramael,

grants manager, greet.ramael@fondsvoordeletteren.be